First National Bank of Kansas City, MO (Charter 1612)

First National Bank of Kansas City, MO (Chartered 1865 - Receivership 1878)

Town History

Kansas City (abbreviated KC or KCMO) is the largest city in Missouri by population and area. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 508,090, making it the 36th most-populous city in the United States. It is the most populated municipality of the Kansas City metropolitan area, which straddles the Kansas–Missouri state line and has a population of 2,392,035. Most of the city lies within Jackson County, with portions spilling into Clay, Cass, and Platte counties. Kansas City was founded in the 1830s as a port on the Missouri River at its confluence with the Kansas River coming in from the west. On June 1, 1850, the town of Kansas was incorporated; shortly after came the establishment of the Kansas Territory. Confusion between the two ensued, and the name Kansas City was assigned to distinguish them soon after.

The city is composed of several neighborhoods, including the River Market District in the north, the 18th and Vine District in the east, and the Country Club Plaza in the south. Celebrated cultural traditions include Kansas City jazz; theater, as a center of the Vaudevillian Orpheum circuit in the 1920s; the Chiefs and Royals sports franchises; and famous cuisine based on Kansas City-style barbecue, Kansas City strip steak, and craft breweries. It serves as one of the two county seats of Jackson County, along with the major suburb of Independence. Other major suburbs include the Missouri cities of Blue Springs and Lee's Summit and the Kansas cities of Overland Park, Olathe, Lenexa, and Kansas City, Kansas.

Kansas City had 43 National Banks chartered during the Bank Note Era, and 40 of those banks issued National Bank Notes.

Bank History

- Organized September 14, 1865

- Chartered November 23, 1865

- Receivership February 11, 1878

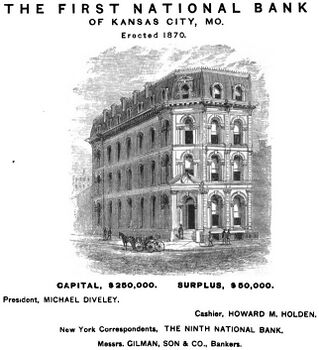

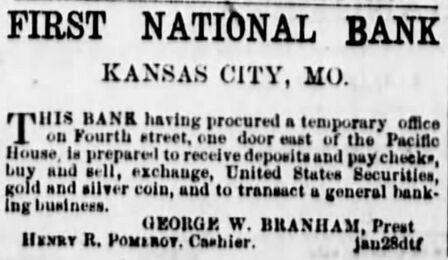

In the last week of November 1865, two new banks were organized, the Fort Madison National Bank, Iowa, with an authorized capital of $75,000, and the First National Bank of Kansas City, Missouri, with an authorized capital of $100,000. The total number of National Banks existing was 1,612, and their total authorized capital was $404,617,323.50. The total amount of National Bank currency issued up to Saturday, November 18th, was $217,385,440 of which $3,273,625 was issued the week prior. At the redemption bureau, $310,150 worth of mutilated currency was destroyed.[4] The First National Bank of Kansas City would occupy a house erected for them at the corner of Fourth and Delaware Streets temporarily until they could build next season.[5] The First National Bank organized with G.W. Branham as president and H.R. Pomeroy, cashier. The bank planned to open for business on December 15th.[6] On December 10th, H.R. Pomeroy, Cashier, announced the stockholders' meeting at the banking house on the second Tuesday of January 1866 between the hours of 10 a.m. and 4 p.m. for the purpose of electing five directors.[7]

In August 1866, Spalding's Commercial College moved to the First National Bank building on the corner of Fourth and Delaware Streets. The college was recommended as one of the best in the West with J.F. Spalding as president and E.H. Spalding as the business agent and director. Attached to the college was a separate department for ladies.[8] In December 1866, H.R. Pomeroy sold his interest in the First National Bank of Kansas City and resigned his position and Howard M. Holden, the purchaser, became cashier.[9]

In March 1867, the directors of the First National Bank were M. Diveley of Diveley & Co.; A.F. Bidwell of Bidwell & Cooper; T.B. Bullene of Bullene & Brother; A.W. Briggs of Briggs, Potwin & Co.; D.M. Jarboe of Jarboe & Green; Kersey Coates, president, K. & N.V.R.R. Co.; P.W. Ditsch, Matt Foster, Wm. St. Clair, and Howard M. Holden. The officers were M. Diveley, president; D.M. Jarboe, vice president; and Howard M. Holden, cashier. The business was under the immediate management of Howard M. Holden, for many years connected with the State Bank of Iowa. The bank had paid-in capital $100,000 and was located on the corner of Fourth and Delaware Streets, opposite the Pacific House.[10]

Panic of 1873

The Kansas City Times, on Sunday, January 10, 1875, described the situation that befell the First National Bank due to the Panic of 1873. Without enterprise and the money to back it, Kansas City would still be the Westport Landing of old. Chief among the men who, by industrial as well as business life, had played important parts in making Kansas City what she is, are Howard M. Holden, Edward H. Allen and their associates, and chief among all the financial institutions of the western country is the First National Bank of this city, of which Mr. Holden is President and Mr. Allen Vice President. Years ago, when the First National first threw its banner to the breeze, from over the door of the unpretentious old building that then stood upon the site that now forms a portion of Adams and Wells-Fargo express block, few if any of our people looked for the steady rise and progress that in 1868 -just two years-resulted in the erection of the finest banking building in all the west, and the establishment of an institution that ever since has been seen as the very bulwark of FINANCIAL SAFETY. Upwards of $50,000 was expended upon the magnificent building, its spacious rooms and general appurtenances being faultless in every detail. Organizing under the National Banking law, the First National, on a paid-in capital of $250,000, that at the end of the first five years no less a surplus than $250,000 lay safe in the vault, thus completely doubling the actual working capital, and showing a net profit over and above regular reserve and dividends of $50,000 a year, or as represented in surplus alone, twenty per cent on capital employed. Such remarkable success, achieved as it was in the face of the usual competition in banking circles, reflected the greatest praise, not only upon the officers of the bank, but upon the board of directors as well, which now as then embraced the very first businessmen of the city. Such for instance as T.B. Bullene and L.T. Moore, of the great house of Bullene, Moore & Emery, T.K. Hanna, of the widely known wholesale dry goods firm of Tootle, Hanna & Co., S.B. Armour of the monster beef and pork packing establishment of Plankinton, Armour & Co., Kersey Coates, the well-known capitalist, Michael Diveley, another capitalist of extended reputation, B.A. Feineman of the extensively known wholesale liquor house of B.A. Feineman & Co., Benjamin McLean, leading dealer in hides and wool, C.A. Chase, capitalist, Joseph A. Bachman, prominent wholesale tobacconist, Joseph Cahn, the enterprising wholesale clothier, C.B. Lamborn, of the K.P. Railway, Octave Chanute, Chief Engineer of the New York and Erie Railway, Edward H. Allen, vice president of the bank and one of the heaviest stockholders, and M.W. St. Clair, assistant cashier, one of the oldest stockholders and connected with the institution.

So rapid was the steady and substantial progress of the First National that a new department especially for savings was established, and in a very short time became a leading feature; upwards of $150,000 being on deposit in the one department alone within six months after its organization. But the savings department was by no means the only enterprise impressing the bank's importance, the First the National Bank's branch at the stock yards became one of the leading banking houses in this section, the amount of money deposited there being simply enormous. The wonderful increase of the cattle business in this city became the marvel of the west, becoming first of all cities in beef packing, and only third in pork packing, being beaten by just Cincinnati and Chicago. Among the depositors were the heaviest cattlemen of the West, and the amount of money daily handled during the busy season was exceedingly large. This confidence of the stock dealers in the First National and its Stock Yard branch was by no means of a transitory character, for daring the dark days of the panic the bank stood faithfully behind them with its large resources. When others failed them, the First National stood nobly to the front, and with one other bank saved from most disastrous rain the stock business of this city. When THE first shadows of September of the memorable fall of 1873 fell over our city the banks, headed by the First National, were never in firmer condition to withstand the effects of the hardest blows that might be delivered, the First National especially holding the confidence of this whole section of country. Day by day came the telegraphic flashes telling of the dire distress in New York and other great centers of finance in the East. Soon came the fearful news of the western direction of the panic's course. The remarkably extended ramifications of the First National's transactions could not but create the most powerful of drains upon its resources, and as bank after bank called for currency, the sterling old First National responded to the demand, meeting every draft presented. As to be expected under such excitement as all labored, people here, as elsewhere, caught the fever of unrest and withdrew deposits at the rate of hundreds of thousands of dollars a day.

At the outbreak of the panic the deposits of the bank aggregated the enormous sum of nearly two million dollars, and as indicative of the true merit that won this confidence it remains to again chronicle the fact that of this amount upwards of a million in cash was paid out over the counter during the height of the panic. Matters finally assumed such shape that the banks of the city met in council and decided to decline payment of checks or drafts until such time as financial affairs assumed better shape. This took effect on September 26th, following the example of banks of St. Louis, Chicago and other large cities. Finally, after having paid down their deposits to a little over half a million, and finding that further enforced collection of their assets must necessarily ruin a large number of the most responsible citizens, the stockholders of the bank, on November 24th, decided to put the bank into liquidation, and on the 25th of November The Kansas City Times published the official announcement of this fact. Had an earthquake happened the shock to the city at large could not have been greater. "The First National failed! No, no, it cannot be," was the cry that arose from the people everywhere. The directors pledged every dollar of their own private fortunes to the credit of the bank, followed up by the President, who also publicly pledged upwards of $200,000 of his own private funds to meet the demands of depositors. If anything had before this been wanting to convince the people that liquidation meant anything but bankruptcy, the voluntary offering of such fortunes as those possessed by Kersey Coates, Michael Diveley, Francis Foster, T.K. Hanna, J.D. Bancroft, Adam Long, W.H. Winants, T.B. Bullene, J.A. Bachman, Dr. Wm. St. Clair, J.N. Packard, Edward H. Allen and Howard M. Holden, to meet any and all just demands, settled the question beyond the shadow of a doubt, and hardly a man or woman who had money in the bank for a moment doubted getting it with interest at the earliest possible moment. None ever questioned the financial soundness of the institution, as it was widely known that the bank had an enormous sum loaned to responsible dealers in cattle, which would be more than realized from the hides alone. It was the difficulty of moving the vast herds of cattle to market at so short a notice that occasioned the stringency with the bank and caused the determination to go into liquidation in order to gain the requisite time to realize upon the securities. Just prior to this action, however, the bank paid over to the treasurer of the city the sum of $135,000, being every dollar due the city from the bank on account of bonds taken on contract to sell. This, as well as the manifest straightforward course pursued by the bank in all matters, despite the trying circumstances of the time, created an enthusiasm throughout the business circles of the city that soon manifested itself in such shape as to leave no doubt of the ultimate raising of the First National banner higher and prouder than ever. So it came about that on December 3rd The Kansas City Times published a call upon the officers of the First National to revoke the order of liquidation and again resume its place at the head of the financial institutions of the New West. Of this remarkable expression of unshaken confidence, The Kansas City Times the same morning editorially remarked: "The names attached to the communication shows how keenly our people appreciate the void occasioned by the suspension of the First National Bank. Among the number are those representing all the leading interests of our city.

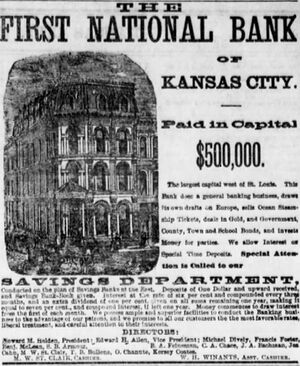

The list embraced merchants, wholesale and retail, manufacturers, packers, commission and grain men, professional men, capitalists and, nearly all the remaining banks of the city. It was a united, harmonious and spontaneous expression of the business interests of Kansas City, assuring the officers and stockholders of our former leading financial institution of the hearth and profound appreciation the people of Kansas City felt for its services in the past, and of their continued esteem and confidence in the First National Bank. It was such a tribute as any institution might feel proud of and grateful for, and such a one as should incite its officers to greater exertions and efforts than could be expected had a different spirit been manifested. This practically settled all questions as to the speedy re-opening of the First National. On December 12th the bank through a committee consisting of Messrs. Diveley, Foster and Bullene, responded to the call by the assurance that the bank would resume on the basis of an increase of capital to $500,000 by the paying in of $250,000 cash, thus relieving and strengthening it, so that when once open it could push out again into active, live and vigorous business. With this report was submitted the report of Special Bank Examiner Talmadge, who was sent by the Comptroller of the Currency especially to determine the exact condition of the bank. Mr. Talmadge's report was indeed a marked compliment to the bank's management, for he officially declared the assets more than sufficient to pay all liabilities and leave its capital wholly unimpaired. The rest may be told in a few words. The First National Bank, on January 1st, 1874, officially announced the formal reopening on the following Monday, the 5th. Every dollar of the additional $250,000 had been subscribed, and with the approval and warm congratulations of Comptroller of the Currency John J. Knox, the First National Bank resumed business. Thus, January 5th was made a day of general rejoicing throughout the city and confidence once more freely restored commerce rapidly assuming its old settled condition.

On Friday, January 16th, 1874, the First National published its first statement under the new order of things, a statement that spoke most emphatically of the wonderful vitality of the institution. With total resources of $1,847,824, its ready cash means were $232,164.17 and its deposits $622,710.17. In addition to this the bank had $280,000 in assets on hand representing the old surplus. This history of the panic as it particularly affected the First National, thinking it most timely on this the opening of the new year. It shows more conclusively than could words of compliment in general terms the gallant manner in which the noble institution weathered the fearful gale that wrecked many older ones. From the day the First National re-opened, the old success had been even more than duplicated. The trial by worse than fire through which it passed endeared rather than estranged friends unequivocally demonstrated by the following statement of business done during the year of 1874 just closed: capital 500,000, surplus 37,000, total deposits for the year $44,921,872.09, average daily deposits for the year $144,909.26, and total exchange sold $17,820,860.00.[11]

In January 1877, the directors re-elected were Michael Diveley, S.B. Armour, C.A. Chase, M.W. St. Clair, Frank Foster, Thos. K. Hanna, J.A. Bachman, T.B. Bullene, Kersey Coates, Benjamin McLean, B.A. Feineman, Joseph Cahn, and O. Chanute. The officers were Howard M. Holden, president; Edward H. Allen, vice president; and M.W. St. Clair, cashier. The bank had paid-in capital $500,000.[12]

On Tuesday, January 29, 1878, a run on the Commercial National Bank caused the directors to temporarily close their doors as a precautionary measure. President Karnes stated that all depositors would be paid dollar for dollar within the next sixty days. That the condition of the bank was as good as anyone could expect and had the officers had any notification whatever of the impending crisis, they could have fortified themselves and the suspension surely would have been averted. The statement of the Commercial National showed total assets of $160,895 with individual deposits $38,886, certificates of deposit $12,586.50, due to banks and bankers $4,790.02.

On Wednesday, January 30, the First National Bank of Kansas City closed its doors. This was necessary due to the shrinkage in deposits of over $350,000, added to the large reduction of the previous few months.[13] Mr. M.W. St. Clair, cashier of the First National stated "there was not a shadow of a doubt but that depositors will receive every cent due them." He added that the reported failures in Topeka were not caused by troubles with the First National and that the Topeka Bank had just $1,900 on deposit there. A list of 83 stockholders was provided of those who held stock in the bank in 1874 when the institution resumed business after the panic. On Thursday there was no sign of panic in the city. The paying teller at the Mastin Bank had hard work to perform on Wednesday and the receiving teller the next day. The report that the Mastin Bank received $75,000 from St. Joseph on Tuesday night was pronounced false by Mr. Thomas H. Mastin. Hon. Seth E. Ward, president of the Mastin Bank was at his post throughout and when thousands of dollars were being paid out to anxious depositors and through all the excitement, he kept his faculties about him and directed the affairs of the bank with his usual forethought and wisdom. Banks and bankers occupied the attention of everyone on the streets, nothing being talked about in the saloons, horse cars or places of business but the late crisis. The reported failure of two banks at Topeka was passed along, but it turned out that only the Topeka Bank and Savings Institution was embarrassed.[14] On February 11th, James T. Howenstein was appointed receiver of the First National Bank of Kansas City and began the process of winding up its affairs.[15]

In February 1878, the old and reliable Missouri Valley Bank sold its bank building in West Kansas City and moved to No. 14, West Fifth Street to the building formerly occupied by the Commercial National Bank. It was under the management of A.J. Banker who brought the bank through the panic of 1873, the strike, and the recent panic while some of the largest financial institutions had to succumb. The Missouri Valley Bank would open Monday morning, February 18th, in the heart of the business portion of the city.[16] The officers were Mr. A.J. Baker, president; A.A. Goodman, vice president; and W.A. Botkin, cashier. This bank was established in Kansas City in 1872. The Missouri Valley Bank was bound to become one of the principal financial institutions of the city.[17] The Missouri Valley Bank would fail in February 1881.[18]

On Saturday, August 3, 1878, the Missouri Valley Bank moved to the First National Bank building where they would continue to transact a general banking business. The people had shown their great confidence in this institution by giving them their deposits in this time of trial. Their new spacious quarters would give them ample room to better accommodate their increasing business.[19]

On September 10, 1878, H.M. Holden, president of the suspended First National Bank; E.H. Allen, vice president; and J.J. Mastin, cashier of the late Mastin Bank of Kansas City, were arrested on the charge of receiving deposits when they knew their banks were failing. They were each held on bail in the sum of $7,000.[20]

On Friday evening, February 28, 1879, the case of State vs. John J. Mastin at Independence terminated abruptly, the result being the acquittal of the defendant. After hearing all the evidence in the case, it was plain to see that there was nothing in it to prove that the officers knew that the institution was in a failing condition. D.C. Smart, vice president of the bank testified that he considered all the assets good. Mr. Peak on behalf of the State said that he had no objections to the jury being instructed to render a verdict of not guilty. It was accordingly done and a verdict of not guilty returned.[21]

The decision in the Mastin trial knocked the bottom out of the cases of the same kind against Howard M. Holden and E.H. Allen of the First National Bank.[22]

In 1893, the branch office of the Kansas City Times was located in the First National Bank building, northeast corner of Fourth and Delaware Streets. The telephone number was 47.[23]

Official Bank Title

1: The First National Bank of Kansas City, MO

Bank Note Types Issued

A total of $307,930 in National Bank Notes was issued by this bank between 1865 and 1878. This consisted of a total of 13,598 notes (13,598 large size and No small size notes). No notes or proofs are known to have survived.

This bank issued the following Types and Denominations of bank notes:

Series/Type Sheet/Denoms Serial#s Sheet Comments Original Series 2x10-20-50 1 - 3360 Original Series 20-50 3361 - 3439

Bank Presidents and Cashiers

Bank Presidents and Cashiers during the National Bank Note Era (1865 - 1878):

Presidents:

Cashiers:

- Henry R. Pomeroy, 1865-1866

- David Mulholland Jarboe, 1866-1866

- Howard M. Holden, 1867-1871

- John Davis Bancroft, 1872-1874

- Madison W. St. Clair, 1875-1877

Other Known Bank Note Signers

- No other known bank note signers for this bank

Bank Note History Links

Sources

- Kansas City, MO, on Wikipedia

- Don C. Kelly, National Bank Notes, A Guide with Prices. 6th Edition (Oxford, OH: The Paper Money Institute, 2008).

- Dean Oakes and John Hickman, Standard Catalog of National Bank Notes. 2nd Edition (Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 1990).

- Banks & Bankers Historical Database (1782-1935), https://spmc.org/bank-note-history-project

- ↑ The Bankers' Magazine, Vol. 26, July 1871-June 1872, p. 996.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sat., Jan. 6, 1877.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Jan. 28, 1866.

- ↑ Washington Chronicle, Washington, DC, Mon., Nov. 27, 1865.

- ↑ Kansas City Weekly Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sat., Dec. 9, 1865.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Dec. 12, 1865.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Dec. 10, 1865.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas, City, MO, Thu., Aug. 2, 1866.

- ↑ Kansas City Weekly Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sat., Dec. 8, 1866.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Mar. 10, 1867.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Jan. 10, 1875.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Wed., Jan. 3, 1877.

- ↑ The Monmouth Atlas, Monmouth, IL, Fri., Feb. 1, 1878.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Fri., Feb. 1, 1878.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Wed., Feb. 13, 1878. The Mastin Bank also failed in 1878.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Feb. 17, 1878.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Thu., Feb. 21, 1878.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Wed., Feb. 23, 1881.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Aug. 4, 1878.

- ↑ The Fairbury Blade, Fairbury, IL, Sat., Set. 14, 1878.

- ↑ Jefferson City Tribune, Jefferson City, MO, Sun., Mar. 2, 1879.

- ↑ Kansas City Journal, Kansas City, MO, Sun., Mar. 2, 1879.

- ↑ The Kansas City Times, Kansas City, MO, Tue., Apr. 18, 1893.